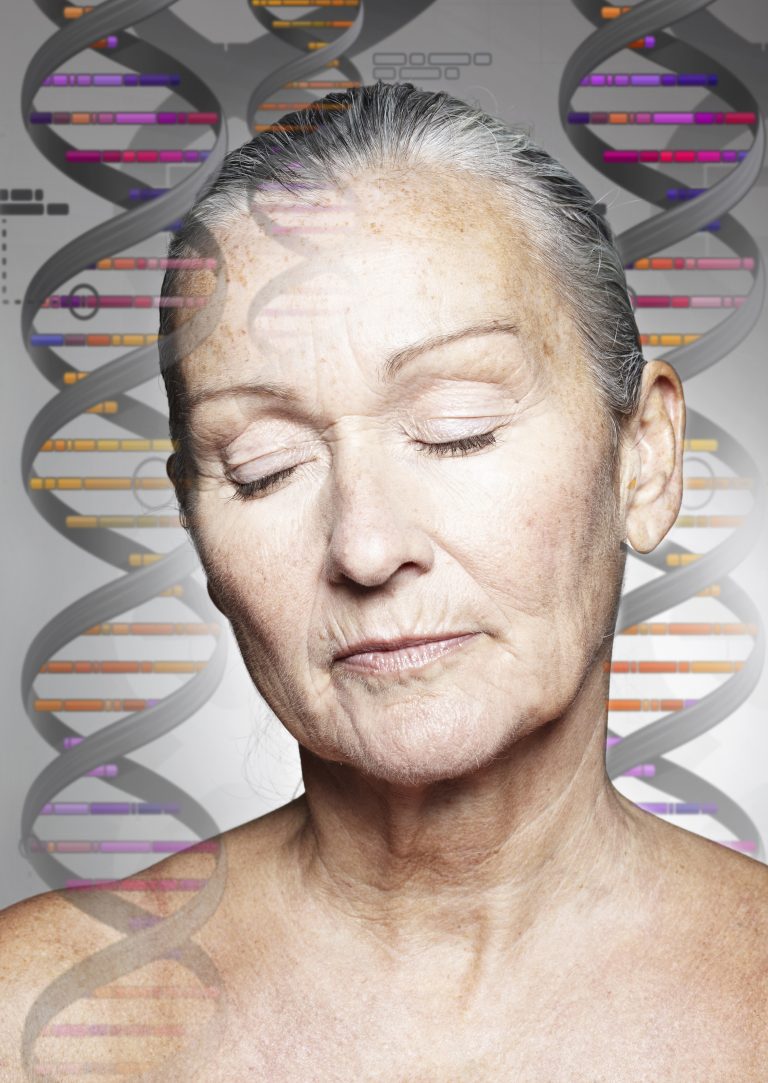

An international group of researchers, led by Stanford University School of Medicine and the Buck Institute for Research on Aging, has developed a way of predicting how likely someone is to develop diseases and symptoms of aging such as immunosenescence, frailty and cardiovascular disease using a deep learning ‘inflammatory aging clock’ fed by immunome data.

Notably, the iAge clock picked out the chemokine protein CXCL9 as being the most significant contributor to a person’s score. This protein is linked to cardiac and vascular aging and further study shows its activity and associated symptoms can be reversed if it is silenced.

“Standard immune metrics which can be used to identify individuals most at risk for developing single or even multiple chronic diseases of aging have been sorely lacking,” said David Furman, Buck Institute Associate Professor and and senior author of the study describing the work in Nature Aging, in a press statement.

“Bringing biology to our completely unbiased approach allowed us to identify a number of metrics, including a small immune protein which is involved in age-related systemic chronic inflammation and cardiac aging. We now have means of detecting dysfunction and a pathway to intervention before full-blown pathology occurs.”

Furman is director of the 1000 Immunomes Project at Stanford, which is seeking to study how a collected set of genes and proteins that make up the immune system –the immunome– contributes to aging and immune function over time.

In this study, the researchers used blood immunome data from 1001 individuals from the 1000 Immunomes Project, aged 8 to 96 years, to program the iAge clock using artificial intelligence. Longitudinal data showing changes in the immunome was available for some of the project participants. The researchers also used data collected from 29 participants of an Italian study, based in Bologna, looking at exceptionally long-lived people (28 of whom were older than 100 years).

The team used a deep learning method known as guided auto-encoder (GAE). “The GAE method is a type of deep neural network that utilizes nonlinear equations and effectively eliminates noise and redundancy in data, yet retaining the most relevant biological information from circulating immune protein data,” write the authors.

They developed a model that appears, on initial testing, to accurately reflect whether people will develop diseases of aging based on their immunome data. Overall, a set of around 50 cytokines seemed to be most relevant for predicting aging health, with CXCL9 levels being most significant.

High levels of this protein, which seemed to rise sharply after the age of 60 in some people, were strongly linked with poor cardiovascular health. However, there is hope for these individuals, as early studies suggest that it is possible to silence the action of CXCL9 and that it could be a target for new drugs in the future.

The older people from the Italian study had very ‘healthy’ immunomes. “On average, centenarians have an immune age that is 40 years younger than what is considered ‘normal’ and we have one outlier, a super-healthy 105-year-old man (who lives in Italy) who has the immune system of a 25-year-old,” explained Furman.

The researchers now plan to work on validating their tool further. They say it could be useful for predicting future health, currently up to 7 years in advance. “That leaves us lots of room for interventions,” concluded Furman.