In a new study lead by scientists at the University of Minnesota and Nantes University Hospital in France, researchers showed that the bacteria in a patient’s gut might predict their risk for life-threatening blood infections following high-dose chemotherapy.

Approximately 20,000 cancer patients receive high-dose chemotherapy each year in preparation for bone marrow or stem cell transplants. Of those patients, typically 20–40% develop blood infections following the chemotherapy—of which 15–30% die as a result of the infections.

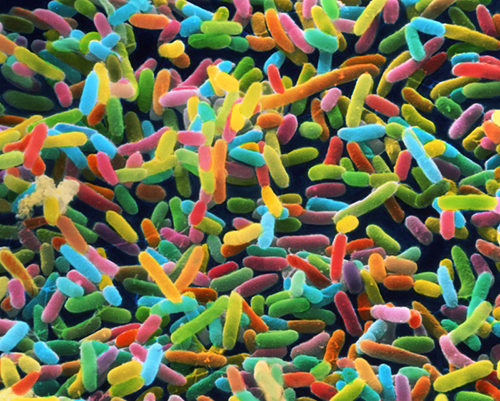

Scientists have hypothesized that bacteria enter the bloodstream through intestinal lesions due to chemotherapy-induced inflammation of the membrane lining the digestive tract. Once the infection begins, a patient’s own immune system is often depleted and unable to fight off the pathogens. Moreover, once this threshold has been crossed, antibiotics often become ineffective.

Currently, there are no good ways to predict which patients will acquire a bloodstream infection; therefore, the researchers in the current study set out to understand how the starting configuration of the gut bacteria, before the patient begins treatment, relates to the risk of bloodstream infection. They collected fecal samples from patients with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma before the patients started chemotherapy and sequenced the bacterial DNA to measure the health of the bacterial ecosystem within each patient's gut.

“We sampled 28 patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) prior to administration of chemotherapy and characterized 16S ribosomal RNA genes using high-throughput DNA sequencing,” the authors wrote. “We quantified bacterial taxa and used techniques from machine learning to identify microbial biomarkers that predicted subsequent bloodstream infection (BSI).”

The findings from this study were published recently in Genome Medicine in an article entitled “Pretreatment Gut Microbiome Predicts Chemotherapy-Related Bloodstream Infection.”

The investigators found that 11 of the 28 subjects acquired a bloodstream infection following their chemotherapy. Interestingly, the researchers discovered that those patients had significantly different mixtures of gut bacteria than the patients who did not get infections.

“We found that patients who developed subsequent BSI exhibited decreased overall diversity and decreased abundance of taxa, including Barnesiellaceae, Coriobacteriaceae, Faecalibacterium, Christensenella, Dehalobacterium, Desulfovibrio, and Sutterella,” wrote the study authors.

Using computational tools, the researchers subsequently created an algorithm that could learn which bacteria are good and bad and then predict whether a new patient will get an infection, with around 85% accuracy.

“This method worked even better than we expected because we found a consistent difference between the gut bacteria in those who developed infections and those who did not,” explained co-senior study author Dan Knights, Ph.D., assistant professor in the University of Minnesota's Department of Computer Science and Engineering and the Biotechnology Institute.

“This research is an early demonstration that we may be able to use the bugs in our gut to predict infections and possibly develop new prognostic models in other diseases,” Dr. Knights added.

The investigators were excited by their findings; however, they cautioned that their results are still based on a limited number of patients with a single type of chemotherapy, at a single clinic. The research team says the next step is to validate their approach in a much larger cohort, including patients with different cancer types, various treatment types, and from multiple treatment centers.

“We still need to determine if these bacteria are playing any kind of causal role in the infections, or if they are simply acting as biomarkers for some other predisposing condition in the patient,” noted lead study author Emmanuel Montassier, M.D., Ph.D., a researcher at the Nantes University Hospital and former researcher at the University of Minnesota.