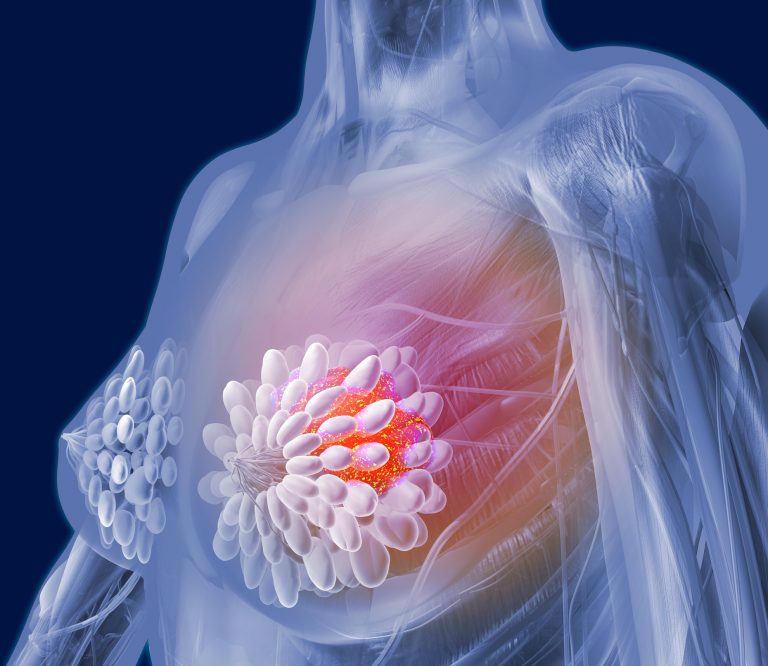

A new study from researchers at the Mayo Clinic Cancer Center and collaborators from the CARRIERS consortium suggests that women over 65 with breast cancer could benefit from hereditary cancer genetic testing. These results, the researchers say, could affect further diagnostic testing, prevention, and treatment.

The study was published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology and the senior author is Fergus Couch, a researcher at the Mayo Clinic Cancer Center.

Couch says that women over 65 rarely qualify for hereditary cancer genetic testing based on current testing guidelines because they are thought to exhibit low rates of genetic mutations in breast cancer genes. In younger patients, the diagnosis is often associated strong family history of breast and/or ovarian cancer, Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry, or estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer. In these high-risk women, the chance of observing a pathogenic variant in a cancer predisposition gene is approximately 10%.

This study was aimed at determining what the likelihood was that older patients might have a high-penetrance gene putting them at risk for breast cancer.

“Most studies of breast cancer genes have not looked at older women, those who were diagnosed over the age of 65,” Couch says. He adds that these studies have mainly tested women with a strong family history of breast or ovarian cancer rather than those in the general breast cancer population. By studying older women from the general breast cancer population, the investigators sought to determine if these women should be routinely offered genetic testing.

The researchers tested 26,707 women for pathogenic variants in established breast cancer predisposition genes. Of these women, 51.5% had had breast cancer, and 48.5% did not. The study matched unaffected women from the large population in the CARRIERS study for age, race, and ethnicity.

“We found that mutations in actionable breast cancer risk genes were present in 3.2% of the women with breast cancer,” says Couch.

When the researchers considered only high-risk breast cancer genes, including BRCA1, BRCA2 and PALB2, they found that 1.35% of women with breast cancer exhibited mutations and that more than 2.5% of women with estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer had high-risk mutations, regardless of their age.

They write: “This study suggests that all women diagnosed with triple-negative breast cancer or ER-negative breast cancer should receive genetic testing and that women over age 65 years with BRCA1 and BRCA2 pathogenic variants and perhaps with PALB2 and CHEK2 pathogenic variants should be considered for magnetic resonance imaging screening.”

Couch notes that: “As 2.5% mutation frequency is often used to trigger genetic testing, these results suggest that all women with estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer, and perhaps all women with breast cancer, including those diagnosed over age 65, should be offered hereditary breast cancer testing.”

He adds that women over 65 with high-risk mutations may benefit from targeted therapies and improved risk assessment for secondary breast cancers. He adds that family members of these women also may benefit from risk assessment. But, women over 65 rarely qualify for hereditary cancer genetic testing based on current testing guidelines because they are thought to exhibit low rates of genetic mutations in breast cancer genes.

“We were not sure what this study of the older breast cancer population would yield, but our results support broader testing, regardless of age or family history,” he says.