Breast cancer researchers in Australia have discovered a new type of immune cell in breast tissue that helps to keep mammary ducts healthy. Using advanced three-dimensional imaging techniques, the scientists, headed by a team at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research, discovered that these ductal macrophages (DMs) monitor for threats in the mouse mammary ducts and help to maintain tissue health by clearing away dying milk-producing cells once lactation stops. As well as being the sites where milk is produced and transported, mammary ducts are also where most breast cancers arise.

The authors suggest that understanding how these immune cells function could provide valuable insights into potential new approaches to treating breast cancer. “We discovered an entirely new population of specialized immune cells, which we named ductal macrophages, squeezed in between two layers of the mammary duct wall,” said Caleb Dawson, PhD, co-senior and first author of the team’s paper, which is published in Nature Cell Biology, in a report titled, “Tissue-resident ductal macrophages survey the mammary epithelium and facilitate tissue remodeling.”

Dawson’s colleagues on the research included Walter and Eliza Hall Institute scientists Geoff Lindeman, PhD, Jane Visvader, PhD, along with Anne Rios, PhD, who is now based at the Princess Máxima Center for Pediatric Oncology, in the Netherlands.

The mammary gland is a dynamic organ that undergoes dramatic remodeling throughout life, the authors explained. The branching ducts bloom to form milk-producing alveoli during lactation, which must then be eliminated once milk production stops. Mammary ducts are of particular interest to breast cancer researchers because this site is prone to cancer development.

Most organs in the body including the brain, liver, lung, skin, and intestine have their own population of macrophages, immune cells that play important roles in regulating infection, inflammation, and organ function within their sites of residence. But while macrophages in breast tissue have been implicated in mammary gland function, “their diversity has not been fully addressed,” the investigators continued.

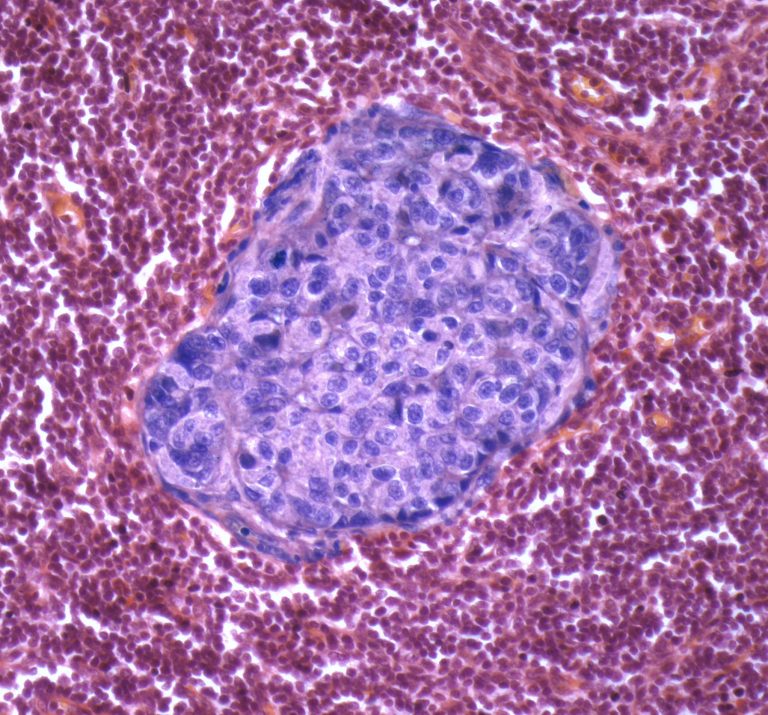

Using techniques including high-resolution three-dimensional imaging and flow cytometry, Dawson and colleagues discovered a type of ductal macrophage that hadn’t previously been identified. The cells exhibited a distinct gene expression profile that implied a phagocytic function, and proliferated during pregnancy and lactation. “DMs were highly enriched for lysosomal genes, which is indicative of a phagocytic role,” they wrote. “Although DMs were rare in adult mammary glands (0.64% of total cells), they expanded 40-fold during pregnancy and constituted 25.7% of total cells in lactation.”

Further investigation suggested that the DMs phagocytose the alveolar cells during early involution. “We were excited to find that these cells play an essential role at a pivotal point in mammary gland function called involution when lactation stops, milk-producing cells die, and breast tissue needs to remodel back to its original state,” Dawson said. “We watched incredulously as the star-shaped ductal macrophages probed with their arms and ate away at dying cells. The clearing action performed by ductal macrophages helps redundant milk-producing structures to collapse, allowing them to successfully return to a resting state.