A rare resistance mutation first thought to appear in melanoma following treatment with a targeted therapy has instead turned out to be hiding in the tumor all along, poised to stop the treatment in its tracks before it could begin, according to a recent study.

Lawrence Kwong, Ph.D., assistant professor of Translational Molecular Pathology at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, led a research team that set out to find resistance mechanisms against a combination of MEK and CDK4 inhibitors designed to treat melanoma that has a mutation in the NRAS gene. The team analyzed a series of biopsies taken before and during treatment to identify the pre-existing mutation, then developed a method designed to target it.

The mutation to the PIK3CA gene initially appeared to be an acquired resistance variation arising after treatment. But by re-analyzing the pretreatment biopsy, Kwong and colleagues were able to establish that it was rare but present from the start, hiding on one side of the tumor. The researchers published their findings March 1 in the journal Cancer Discovery.

NRAS mutations occur in 15% to 20% of melanomas. The treatment combination of MEK and CDK4 is often effective against these tumors at first, until resistance emerges.

“Our study is the first to measure multiple regions in pre-treatment tumor biopsies at high resolution and then track the resistant mutation over years of treatment through six biopsies,” Dr. Kwong said in a statement. “We are able to say that this mutation started out rare and then rapidly expanded as the MEK/CDK4 inhibitors killed off a large number of non-resistant cells.”

According to MD Anderson, that finding helped Dr. Kwong and his research team establish that pre-existing mutations like the one they found can lurk in a patient’s tumor 10 times more rarely than previously thought, yet still cause rapid drug resistance.

That raises the possibility that even more rare mutations exist in other patients, less detectable than what current technology would allow: “Right now, when we detect a resistance mutation after treatment, we often don’t know whether it came out of nowhere as a new mutation or was pre-existing but undetected in the original tumor,” Dr. Kwong said.

Understanding that difference, he added, could guide treatment to make it more effective, earlier. However, identifying rare mutations that are geographically isolated on a tumor will require an improved approach to analyzing biopsies.

In the study, a 59-year-old woman with stage III malignant melanoma was found to have an NRAS mutation in her tumor. She was enrolled in a clinical trial combining a MEK and a CDK4 inhibitor.

After an initial partial response of a 39% reduction in tumor burden, resistance to the treatment arose swiftly. The disease progressed and spread.

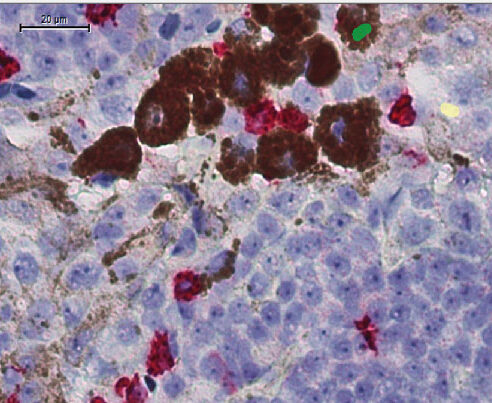

When researchers carried out post-treatment whole exome sequencing of the resistant tumor, they found a mutation to PIK3CA known to promote tumor growth. Since the mutation was detected only 16 days after the onset of treatment, Dr. Kwong and colleagues re-examined the pretreatment biopsy, which sampled a single region of the tumor and had not found a PI3KCA mutation.

The team found PIK3CA mutations in three regions after examining seven regions of the biopsy sample, using an amplification method developed by David Zhang, Ph.D., assistant professor of Bioengineering at Rice University, and a co-author of the study. The pre-existing mutation was both rare and geographically dispersed in the tumor, making it hard to detect by sampling a single region.

The findings suggested that multi-region sampling would expose pre-existing resistant cells, an approach that Dr. Kwong said would not be cost-effective now, but is likely to become more feasible as the technology develops.

The mutation could also be detected by isolating circulating cell-free DNA in the blood after resistance developed, making it a potential target for liquid biopsies that are under development, the researchers added.

Since adding a PIK3CA inhibitor to the MEK/CDK4 combination is likely to be too toxic, investigators instead studied 300 proteins, discovering targets that might be present in more than one of the three cancer-promoting pathways. They found all three of the pathways met at a single spot, a protein called S6. Treating mice with an S6 inhibitor re-sensitized them to treatment with the MEK/CDK4 combination, restoring the drugs’ ability to shrink the PIK3CA mutation-bearing melanomas, the researchers reported.

The study suggests that an optimized human version of the S6 inhibitor seen in mice would be a potential target for human drug development, but such an inhibitor has not yet been developed.

“One of the main questions in cancer drug resistance is how often it comes from a pre-existing or a completely new mutation” added Gabriele Romano, Ph.D., a postdoctoral fellow in Translational Molecular Pathology at MD Anderson, and the study’s first author. “Our study helps define some of the parameters and tools that will be needed to answer this tricky question.”

The study was funded in part through MD Anderson’s Melanoma Moon Shot™—part of the institution’s Moon Shots Program™, an effort aimed at accelerating scientific discoveries to reduce cancer deaths via the development of innovative methods for prevention, early detection, and treatment of different cancer types.

Other funding sources for the study included MD Anderson’s Cancer Center Support Grant from the National Cancer Institute (CA-16672), the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas, the Dr. Miriam and Sheldon G Adelson Medical Research Foundation; and grants from the National Cancer Institute (RO1CA203964, RO1CA182635, and 4PO1CA163222-04), the University of Texas Rising STARS Award and the Melanoma Research Alliance Young Investigator Award.